By 2023, it is likely that many natural gas consumers in Ontario will pay more in carbon charges than they pay for natural gas itself. The Supreme Court of Canada ruling on the constitutionality of federal carbon legislation, and the establishment by the federal government of a carbon price schedule to 2030 have together firmed up the carbon price signal. The result has been an intensification of planning on the part of many energy users to decarbonize their energy supply to mitigate these increased costs.

Planning for the Energy Transition

How should one plan for such large, potentially costly, and unprecedented changes? As D-Day commander General Eisenhower said, “Plans are useless, but planning is indispensable”.

The value of planning is that it forces the planner to look at the many interacting parts, the dependencies and the contingencies that must be considered if success is to be achieved. It is unlikely the plan as first conceived will be implemented unchanged. But the process of planning equips the organization to anticipate possible challenges or obstacles that will arise, understand their impact and be confident in their ability to pivot to a new, viable solution.

For many organizations embarking on the energy transition pathway, the tendency is to look at specific parts like a gas-fired boiler and say “let’s replace it with an electric one.” Or “let’s add solar PV to our mix to make it greener”. Or “the answer to our heating problems is geothermal”. An equipment manufacturer or service provider will be more than willing to help you decide that their technology will reduce your carbon footprint or save cost. The danger in jumping to these tactical decisions without a comprehensive plan is that they only deal with some isolated elements of what is an interrelated system. More complex interdependencies that will determine the eventual ongoing operating and capital cost impacts are overlooked. And critically, a broader impact assessment may reveal that the specific measures do not end up reducing much carbon at all.

An Energy Transition Framework

So how does one deal with the multitude of options, costs, and technologies available today and in the fast-coming future?

Jupiter uses a three-element framework to help clients navigate their technology and operating options while understanding the impacts on future energy costs and carbon emissions.

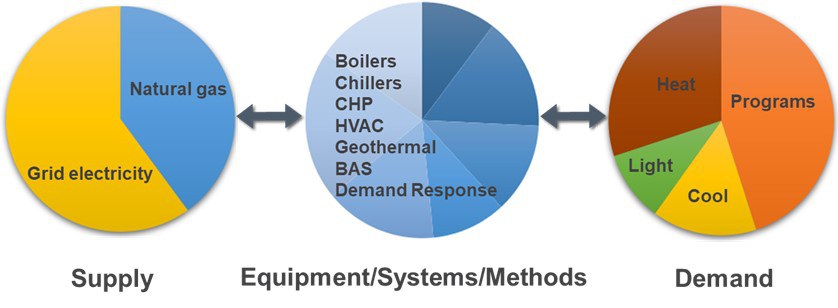

The three key elements are interrelated, integrated and act as system:

- Energy supply

- Equipment/systems/operating methods

- Demand

Each element has its own independent factors that need to be assessed, with key assumptions and with awareness of uncertainty. Decarbonization strategies must consider the interplay between these elements.

Start to plan by examining opportunities to reduce demand, which is the driver of all the other elements and so yields benefits across all elements. If you can reduce facility heating demand with energy efficiency retrofits, building envelope and other improvements then the benefits create a multiplier effect as they ripple back through the equipment and energy supply cost elements. In Ontario for example, strategies that enable demand control can also be sources of revenue from the IESO’s Demand Reduction market, revenue which can offset other transition costs.

In the equipment element of the framework, a commonly considered strategy is switching out a gas-fired boiler or even a gas-fired cogeneration facility with an electric boiler. In Ontario, the annual energy cost of this change would be significant and in Alberta, the price volatility and budget volatility during the winter heating months would be notably amplified by the increased demand of the electric boiler. But how much will the carbon emissions be reduced? Ontario’s electricity grid will become more carbon intensive over the next several years, with gas-fired generation on the margin much of the time. Is the organization foregoing low-cost gas-fired self-generated power for higher cost gas-fired generation from the grid? In any Canadian province, are cold climate heat pumps an alternative to electric boilers to reduce cost impacts, as they are much more than 100% efficient, though they may not scale to the size required of some projects?

Decarbonization planning should recognize the inevitability of unexpected changes in the future, like new technologies or supply policy changes. You need flexibility in any pathway to prevent getting boxed in.

The strongest business case for a decarbonization and electrification strategy includes analysis and quantification of the impacts on all elements as a system which mitigates risks and surprises. We have seen many strategic decisions focused on only one or two elements while neglecting the third. Neglecting to understand how the three elements work together creates unintended cost and risk consequences.

Finally, how much is an organization willing to pay for carbon abatement? What is the marginal cost of the next increment of emissions avoided? How can one determine how much is too much when considering the different options? These tradeoffs, decisions and plans can be made better when informed by a system-level, integrated approach where all options and assumptions are incorporated as in the three-element framework.

-

Electrify your operations to reduce GHG emissions? Perhaps not that simple.

On Ontario's electricity grid, natural gas generating units are increasingly called on to provide power, even in off-peak hours. The trend has significant implications for those looking to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through electrification.

read more -

Generational change: Experienced senior staff are leaving

Many organizations face a growing challenge as senior employees leave the organization, taking with them significant knowledge and experience. Outsourcing expertise can be an effective way to fill the knowledge gap quickly, while lowering costs and reducing risks.

read more -

Electricity price behaviour in Ontario is changing

Increased reliance on gas-fired generation will lift hourly electricity prices in Ontario. Higher HOEP and greater demand will lower Global Adjustment costs. It's a dynamic Ontario consumers have not seen in a long time.

read more